How to think (better) 🧠

Protecting the mind against AI-related cognitive decline

Does using AI make you dumber? A recent MIT study on the effects of ChatGPT use on your brain found indications of “an accumulation of cognitive debt” among prompters. This means that the benefit of short-term effort avoidance, through reliance on large-language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, comes with a long-term cost. This isn’t new.

In 2011, a phenomenon dubbed ‘the Google Effect’ was identified:

“The study found that when people expect to have access to information in the future, such as by looking it up, they are less likely to remember the info itself and more likely to remember how to find it again. In other words, the internet has become an external memory system.”

The tools we use shape how we think and use our brains. As AI is upending the way we interface with the internet, we need to protect ourselves from the more dire findings and conclusions from the MIT study, which had people write essays:

“Over four months, LLM users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.”

Of course, this underperformance depends on the nature of our interaction with LLMs. For example, if you’re setting yourself challenges to build your own apps with AI, like I’m doing this month, you may indeed experience benefits. But let’s hedge our bets. As a species that thrives on efficiency, we will always err towards laziness and lower effort. This led me to today’s topic…

How to think (better)

Whether you know it or not, I bet you have some favourite techniques. Here’s what I’ve found works well for myself. I’m curious to learn about what works for you in the comments.

Ed Boyden: Synthesise new ideas constantly

In a 2007 blog post, Boyden, a neuroscientist at MIT, shared his advice with students on how to think. Occasionally, I refer back to this post as it’s concise and filled with good reminders. Boyden recommends synthesising:

“Never read passively. Annotate, model, think, and synthesize while you read, even when you’re reading what you conceive to be introductory stuff. That way, you will always aim towards understanding things at a resolution fine enough for you to be creative.”

I love this because it encourages a proactive attitude towards activities we might otherwise undertake passively. It’s also a good way to stave off boredom. A key reason I write is that this synthesis assists me in thinking and processing.

Metacognition

Thinking about thinking is known as metacognition. It exists in various forms and systems that work together, but simply put, it involves becoming aware of your thought processes.

You can enhance your metacognition through journaling, mindfulness exercises, and also by talking aloud when you’re engaged in tasks. In software engineering, there is something called rubberducking, which involves placing a rubber duck on your desk and, as you work through engineering problems, explaining them to it as if guiding the duck. This often helps to clarify thoughts or identify areas you’ve overlooked.

Dancing (or other physical activities that require a lot of coordination)

This has been a big one for me over the past year. I’ve always loved dancing, but had been limiting myself to the confines of raves. Last year, I decided to start trying various types of dance classes and workshops, ranging from ecstatic dance to more contemporary choreography. And it was humbling…

Seeing the dance instructor make the moves, knowing exactly what you need to do, and then somehow finding your mind struggling to coordinate and keep your body in sync with the rest of the group… Oof. Slamming my joints into the floor unelegantly wore on my energy, but it’s not on par with the mental exhaustion.

Just like your body can feel tired from a workout, so can your mind. Look for activities that make your mind tired in that way. That’s the feeling of your mind making new connections and training its weak spots.

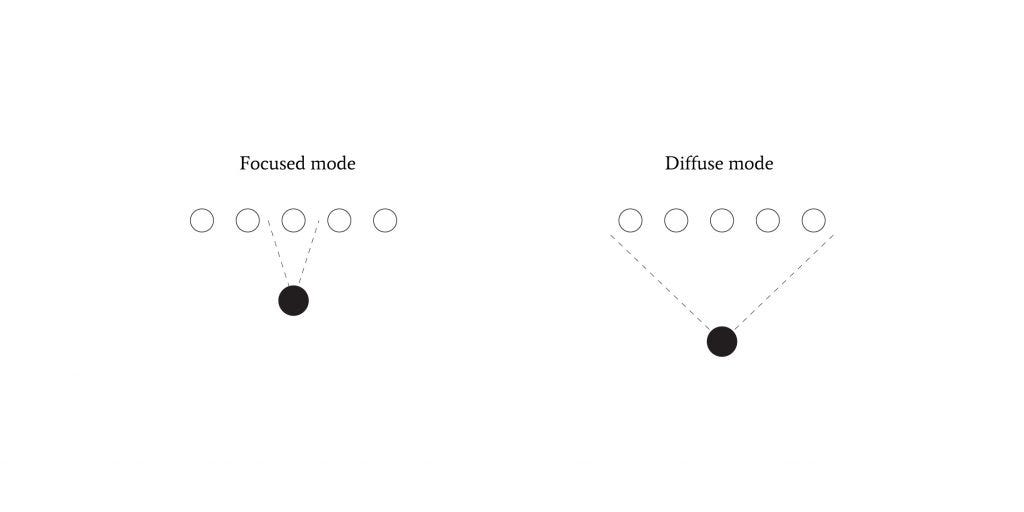

Intentional switching between focused & diffused thinking

I love tasks that just suck me in. For me, that can be writing, building apps, DJing, or other creative pursuits. Writing, in particular, draws me in as it engages different modes of thinking:

Focused: doing research, penning down my paragraphs, or editing my newsletter before sending it out.

Diffused: looking for connections between themes, planning article structure, etc. These may sound like focused activities, but some of these may occur in the back of my mind while daydreaming over days or weeks, or during a brief break from writing while I make some coffee.

I find that it prolongs my concentration to spend about 20 minutes in focus mode, followed by 5 or 10 minutes of diffuse thinking mode.

We do this switching naturally, but by bringing intention to it, we can develop good thinking habits.

Think about thinking in the age of AI

It’s the Information Age. What started with an abundance of information has now evolved into such advanced mastery of computation that we can outsource activities to AI that were previously reserved for our own brains. What it means to think and use our minds in this decade differs from what it meant in the last decades.

But don’t panic: our brains are the same as they have been. It’s the context that has changed. When we find ourselves working from home more often, we might go for walks more frequently to stay fit. How will you keep your brain fit as it metaphorically gets to stay home more often?

(◕‿◕✿) For your left mouse button

Jenny Gross, for the NYT, wrote about a Belgian collective called Papy Booom, who takes the elderly out clubbing to help fight loneliness. They mostly had a blast.

is a fair fashion campaigner. She writes and speaks regularly about the harms of fast fashion, including by bringing attention to the increasing volume of cast-off clothing entering the global south for ‘recycling’. As much as 40% of this clothing becomes waste, but these places often lack adequate means to deal with such high levels of waste.

This means the garments, which often contain synthetic materials like plastics, end up polluting the environment. Venetia offers a highly confrontational account of our consumption habits (with action points).I’ve been exploring ‘ambient jazz’ lately. This write-up by Philip Sherburne for Pitchfork provides a great introduction. If you feel like you’ve done your share of reading for today, the article is accompanied by a playlist on Spotify or Apple Music, so you can explore with your ears instead.

One thing I find about the world of AI is the question of whether to trust what the AI is telling me. I'm quite certain I'm letting the AI slip bullshit into my mind, the issue is that I don't know which things are bullshit and which aren't.

Part of the issue is that it would be really nice if you could trust it. It would save so much time. So you're constantly faced with the choice between concluding you trust it enough or doing hours of work fact-checking.

I usually end up concluding that I trust it.