Is AI turning music streaming services into comment sections? 💬

Spotify, AI-generated music, the far-right, and the century-long squeeze that led to this moment

Suddenly, Spotify’s viral chart for the Netherlands saw itself populated by AI-generated far-right music. Songs with titles like “Fuck you! Leftist fuckers!”, “Just call me far-right”, and “If you don’t like it then leave!”.

This happened against the backdrop of the recent Dutch parliamentary elections following the fall of a populist right-wing government. In the run-up to these elections, anti-asylum seeker demonstrations erupted in violence multiple times, with one in The Hague leading to torched police cars and the smashing of the party office windows of the Netherlands’ liberal democratic party, D66.

Those far-right AI songs? Not against the terms of service, according to a statement by the music streaming market leader, reports Dutch newsletter AD (translation mine):

“Spotify does not allow work that “incites violence or hatred against protected groups or promotes violent extremism” with an “immediate risk” in the real world. According to Spotify, the song does not do that.”

This definitely made me scratch my head for a moment, at the risk of entrapping my fingers in my luscious though oft-tangled locks.

Last week, another music streaming service, Deezer, reported receiving over 50,000 fully AI-generated tracks per day. At this rate, that would mean nearly 20 million per year, or 38 per minute.

With anyone able to generate tracks with a few clicks, streaming services will have to reckon with moderation, lest they become comment sections.

Popular music = economics

Music has undergone massive changes over the past 150 years. Popular music, as in music that people in your community are all likely to know, was folk music. Songs that travelled. Songs that a person in your community was best at performing. Some songs would be new and specific to your community, and others might be centuries old.

Then the recording came. And mass consumption.

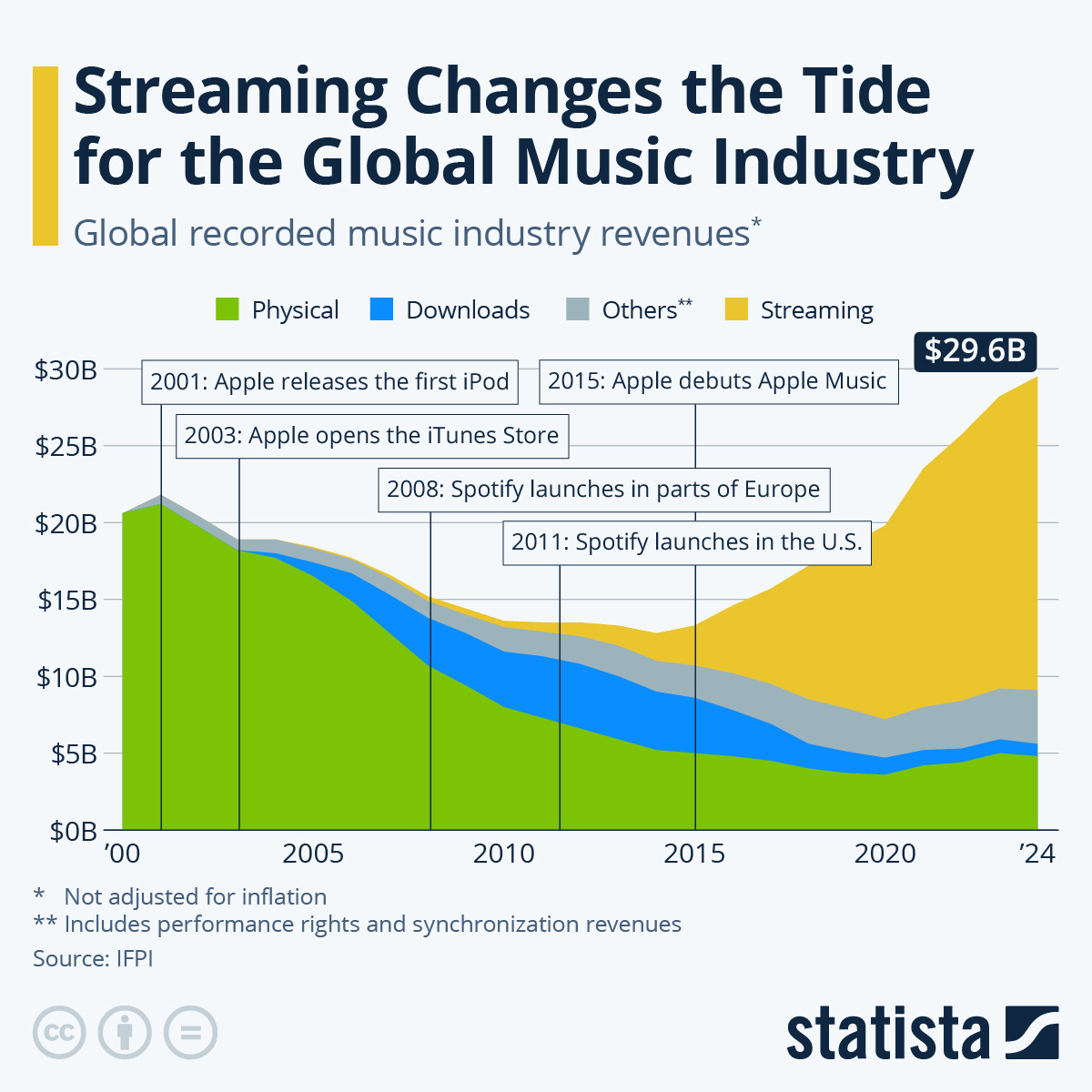

Instead of a participative music culture, most music was primarily consumed: through records, then downloads, then streams. Music as a format shifted, too: from albums, to single-track downloads and iTunes playlists, to infinite personalised recommendation-based radio stations.

Music creation is also a tale of consumerist culture and economics. Big bands got dethroned by pop and rock bands, who in turn lost their place at the center of popular culture to hiphop (or pop influenced by the genre): economically much more efficient with drum machines & microphones. And then electronic music blew up globally, which can be made with just a laptop and performed by DJs travelling with not much more than a USB drive.

This is not intended to read like a tale of cynical greed, but rather one of systems and incentives. The system of consumerism rewards economic efficiency until every last cent of profitable return has been squeezed out.

In the process of the economic squeeze, a few genies have been let out of the bottle, undermining the system built by the recording industry itself.

Genie in a out the bottle

Around the time Christina Aguilera released her breakthrough hit Genie In A Bottle, the systemic incentives toward cost-efficiency had come bearing down on the recording industry. This happened most notably through online technologies, which reduced the cost of music reproduction and distribution to almost zero. Many music fans chose to sail the high seas of piracy. We all know the story from there: over a decade of decline in recorded music revenues.

The other genie that had been let out of the bottle was that almost everyone could now make music. Got a PC? Got an internet connection? Now you can have a small studio on your laptop, whether by purchasing music production software or donning a virtual eye patch and sailing the high seas (which is how many producers of that generation got started).

No longer did you have to get an A&R at a record label to ok your project for it to have a chance to be recorded and heard by people. Just do it yourself.

The 2008 documentary RiP: A Remix Manifesto, featuring mash-up artist Girl Talk, perhaps captures this cultural moment of the late 2000s best.

Slowly, active participation in pop culture returned to the mainstream through remix and mashup culture, which many corners of the record industry vigilantly tried to fight until it found ways to monetise it through content identification systems that redirect digital revenue streams to rightsholders.

Online, popular music started behaving a bit like folk music again. Participative. Communal. And context-specific.

Over time, these remixes could behave like memes. Music catalogues made their way into Instagram Stories and TikTok. If you’re too young to remember the internet before that era, it’s hard to make clear how restrictive things were.

Music creators, who could now really be anyone, started gaming the existing structures. Some through nefarious means like botting streams, or by now-common industry practices like releasing loads of short tracks, so you rack up higher streaming counts (and royalties), or releasing so regularly that you never fall off of people’s Release Radar playlists.

The result:

Many tens of thousands of tracks are added to streaming services daily.

And this was before AI.

We should not be surprised that music has lost many of its 20th-century characteristics.

Entire industries have focused their energy on ensuring that music is ever easier and ever cheaper to make and distribute, whilst hyperpersonalising it to ensure people have something to listen to all the time. “Music for every moment”, as Spotify’s marketing campaign slogans rang.

Generative and adaptive music was always going to happen.

Music as language

In a way, we’ve come full circle. Music has historically been one of humanity’s most important venues for storytelling. In recent centuries, music has gone through an extraordinary process of professionalisation. In the 20th century, it became incredibly difficult for the average individual to tell stories through music that sounded on par with music supported by record labels.

The economics pursued by the record industry ultimately undermined their cultural monopoly by weakening their gatekeeper position. If anyone can create & distribute music cheaply, creators don’t have as much need for record companies’ financial resources. So the record industry went from taste-making to taste-chasing, supporting artists at slightly later stages of their careers, often after they could show traction with fans or the ability to go viral.

Radiohead’s Thom Yorke once called Spotify “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse.” His critique came in the context of a hopeful era of the web. He thought music didn’t need another intermediary, and certainly not one as closely aligned with the major labels’ interests. Ultimately, the battle for the web was won by middlemen who sit between artists and fans: Meta, TikTok, Google / YouTube, Apple Music, the list goes on. For what it’s worth, I think it’s good that at least one of these intermediaries has its roots in music. But I digress.

Thom Yorke called it. He thought the recording industry was losing relevance compared to its role in the previous century.

Now we’re seeing that play out.

If everyone can express their ideas through music with just a few clicks, what role do the recording industry’s streaming services have?

The choices streaming services face

The Netherlands’ viral charts on Spotify turned into your typical 2025-era internet comment section. This was only changed after the distributor of most of the far-right AI tunes, DistroKid, became aware and decided to pull the plug on them.1

What’s worse is that 97% of listeners struggle to distinguish between AI-generated and non-AI music. That means the emotional impact of generated songs will, at least upon discovery, be similar to ‘human music’.

I believe that music in the 20th century was an anomaly. It was a product of an era of mass media and a time when few people had the means to produce and distribute music. As we moved into networked media, music could become small again: relevant only to specific contexts. This can be a national political context, but also a particular WhatsApp group. Memes already behave this way, because they’ve long been easy to create with image editing. Now it’s music’s turn.

And this is not new. I used to be on hiphop forums where people would record tracks to battle each other, for an online audience of maybe a few hundred people. This was in the early 2000s, when computers didn’t come with built-in mics or sound cards that made recording easy.

The future already happened, and now it is taking hold of popular culture.

At the start of 2024, I published a piece titled Will AI correct the anomaly of the 20th century music business? in which I concluded:

“We might comfort ourselves with the thought that we’re not there yet, but if the last 2 years have shown us anything it’s that things can move fast. Lightning fast.

In the introduction I mentioned the question “what happens when anyone can just make a song with a text prompt?” but I believe this question to be irrelevant, because before we can formulate a meaningful answer, the above will have already come to fruition.

Even with the above just around the corner, we should act like we are already there. What we believe to be true in the future, is true now. If we hold it to be evident, inevitable, the best thing we can do is to behave like it is already the case, at least part of the time.”

Streaming services will have to pick a strategy.

Are they going to be comment sections? Will they be vestiges of the type of recorded music that emerged in the 20th century? Will generative music services like Udio (now licensed by the world’s largest major label) and Suno (still under legal pressure) become the platforms for this type of music instead?

There are many, many roads.

Reasons to stay Calm & Fluffy

My goal with this newsletter is to bring calm to people. That means explaining technology and exploring paths forward. While topics like far-right violence and AI displacing human-created music in the charts might not be the calmest and fluffiest of topics, I find it important to address these issues regardless.

What makes me hopeful is this:

More people are making (recorded) music than ever.

Many people, especially musicians, are dissatisfied with the status quo of music streaming. This is not something that is fixed. As a matter of fact, I think music is going through its most significant transformation in decades.

The future is uncertain. This means YOU get to play a role in it. Your imagination, your creativity, and your expression can all play a part in it.

What is surfacing today feels like the future, but some of it has been decades in the making. What is the future that is happening now that nobody is paying attention to?

What do you want to see? What do you want the future to look like?

Let your light be the spark.

જ⁀➴ for your curiosity જ⁀➴

Want a deeper dive on the above topic? Travel back to the future with me and see how well my predictions from early 2024 have held up so far:

YouTuber The Plain Bagel is a level-headed financial analyst who regularly challenges the myths peddled by ‘finfluencers’ and creates educational videos on personal finance and investing. In a recent video, he addresses the question: Are we in an AI bubble?

I get why people jump to AI to generate some artwork for their latest Substack post or a presentation. I’ve been there too. I often find that AI-generated artwork undermines the creativity and original thinking in someone’s work.

To make it easy to give your work the visual support it deserves, Jordan Acosta has put together a great piece on free-to-use picture resources for writers, with paintings and photography from around the world (+ more in his follow-up post).

ᕱᕱ For your ears ᕱᕱ

One for the technoheads… or the techno-curious. Nowadays, DJ slots are often limited to 60 or 90 minutes, leaving performers little room to truly take their audience on a journey.

For this reason, every once in a while, I’ll pop over to Berghain, where DJs get 3-hour slots, so they have room to express and experiment.

One regular name to perform there is Dustin Zahn, who put together this excellent set in 2013, back when the average tempo hovered around somewhat lower BPM ranges than today.

A music distributor is a service that lets people share their music on streaming services for a small monthly fee and/or a percentage of revenue. Unlike popular belief, musicians can’t just make a Spotify profile and upload music directly to the service.